Deep Dive: Custom Decryption, Fileless Execution, and the Evolution of DarkTortilla

By Securonix Threat Research: Shikha Sangwan

Published: October 8, 2025

Last Updated: November 19, 2025

Overview

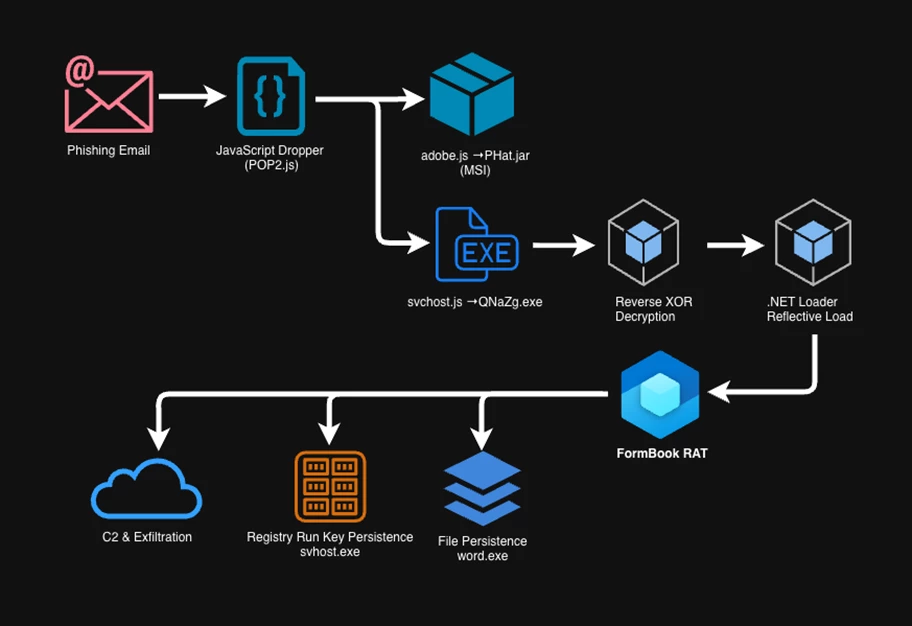

The Securonix Threat Research team analyzed a highly sophisticated DarkTortilla-based malware campaign, codenamed CHAMELEON#NET, which uses a multi-stage infection chain combining custom encryption, reflective .NET loading, and multi-layer script obfuscation to deliver the FormBook RAT payload entirely in memory.

This campaign demonstrates a strategic combination of social engineering, script-based evasion, and modular payload design, with each stage crafted to bypass detection and maintain stealth.

Introduction

DarkTortilla is an evasive, modular .NET loader active since 2015 and responsible for distributing a range of commodity malware such as AgentTesla, AsyncRAT, and FormBook. Its modularity and heavy obfuscation make it one of the more persistent frameworks in circulation.

The CHAMELEON#NET campaign targets organizations within the National Social Security Sector, using realistic and well-crafted phishing emails to trick victims into downloading what appear to be legitimate files. The infection chain relies on heavily obfuscated JavaScript droppers, which lead to the execution of a VB.NET loader. This loader uses a custom XOR cipher to decrypt an embedded DLL and reflectively load it into memory, ensuring that the payload never touches disk.

The decrypted payload is the FormBook RAT, which establishes persistence, disables security mechanisms, and maintains long-term control of compromised systems. This analysis will break down each stage of the attack, from the initial JavaScript dropper to the final in-memory execution of the FormBook RAT.

The Infection Chain

Initial Access: The Malspam Lure

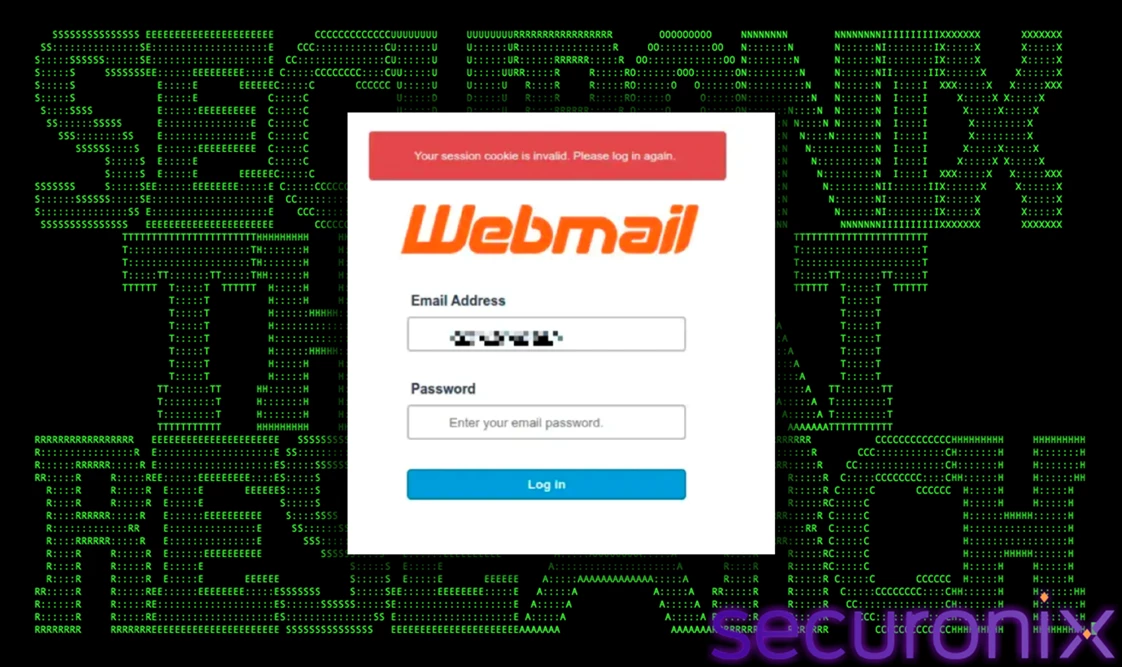

The attack chain begins with a carefully crafted malspam email. These emails direct victims to a fraudulent webmail portal that mimics a legitimate service, prompting them to enter their Social Security (SSA or SSI) institutional credentials. This serves the dual purpose of credential harvesting and acting as a gatekeeper for the malware payload.

Figure 1 – Fake webmail portal used for credential harvesting and payload delivery

Once the user submits their credentials, they trigger the download of a compressed archive named 81__POP1.BZ2. By this stage, the victim is already in a task-completion mindset, expecting to receive a document such as a PDF or Word file related to a grant or internal communication.

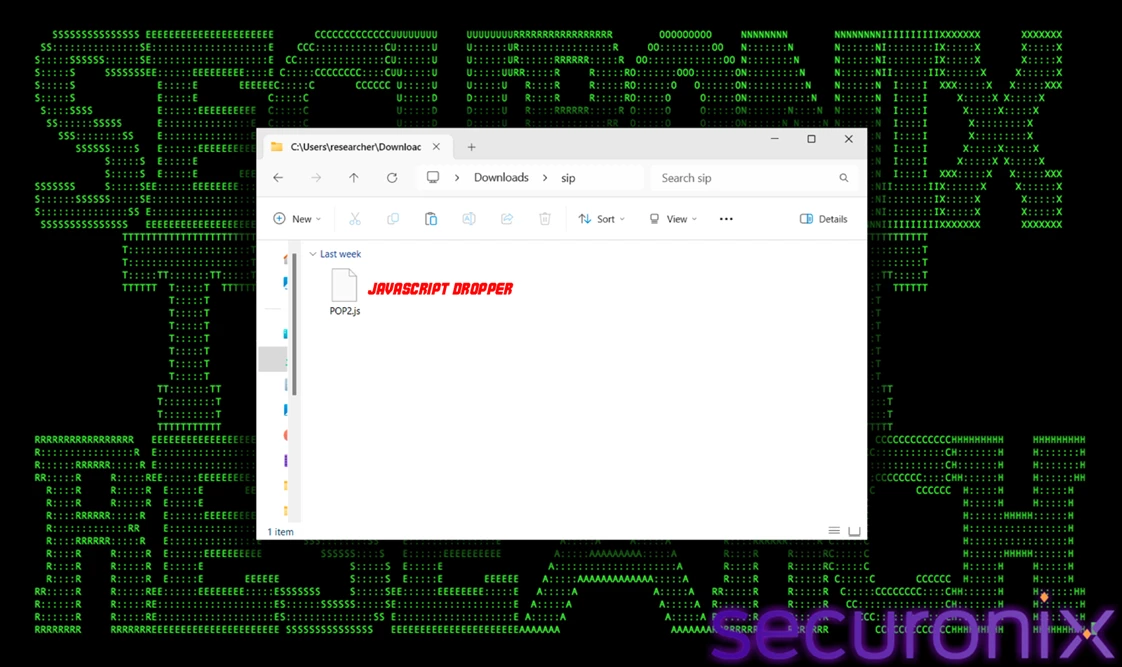

Inside the archive is a malicious JavaScript file named POP2.js. The name and extension help maintain the illusion of legitimacy — it looks like a benign script or text file related to the document workflow. The victim, believing it contains the promised information, double-clicks to open it — initiating the infection chain.

This is not random spam; the email content appears urgent and time-sensitive, and by the time victims reach the fake portal, they have been psychologically primed to trust the process.

Figure 2 – Extracted JavaScript dropper from archive

Stage 1: Multi-Stage JavaScript Dropper

When executed, POP2.js acts as a multi-stage dropper. Its code is heavily obfuscated with multiple layers to defeat static antivirus detection. It contains meaningless variables, unused assignments, and arithmetic-based character generation. Critical strings such as ActiveXObject references are constructed dynamically at runtime using functions like String.fromCharCode().

This technique ensures that signatures based on static analysis fail to recognize the true intent of the script.

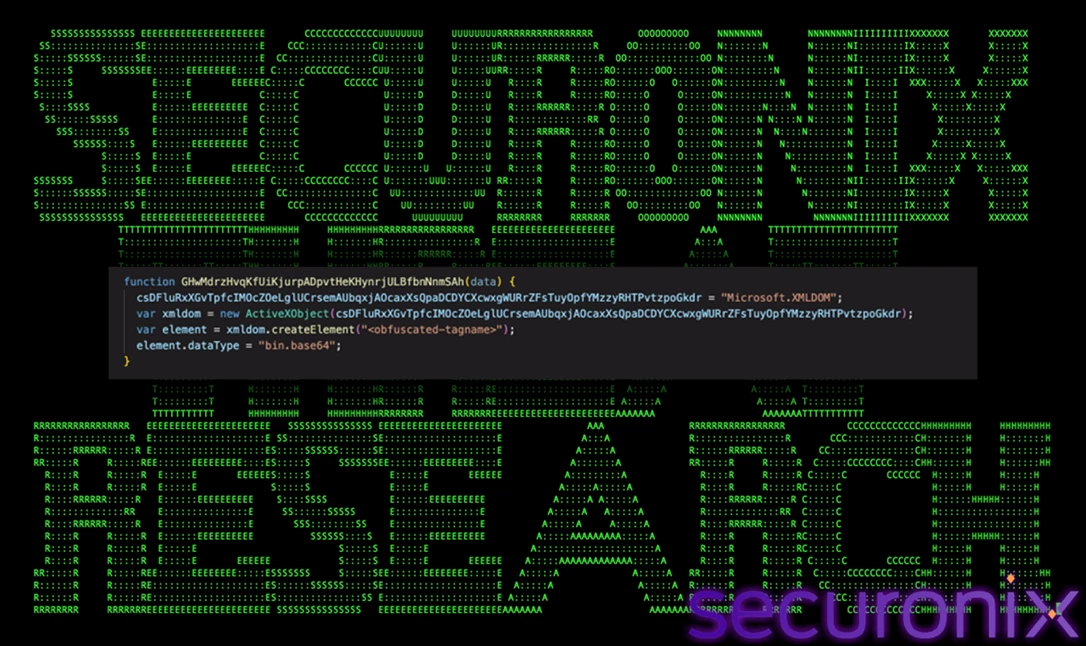

Figure 3 – Heavily obfuscated dropper code

After deobfuscation, the script’s true functionality is revealed. It relies on a combination of ActiveX objects to decode and deploy additional payloads embedded as Base64 strings:

Scripting.FileSystemObject– Retrieves the user’s temporary directory (%TEMP%).Microsoft.XMLDOM– Decodes embedded Base64 strings. The script creates an XML element, sets itsdataTypeto “bin.base64”, assigns the Base64 string to itstextproperty, and retrieves decoded binary data from thenodeTypedValueattribute.ADODB.Stream– Writes the decoded binary data to disk.

Figure 4 – Payload decoding sequence

Once decoded, the script writes two new JavaScript files — adobe.js and svchost.js — to the %TEMP% directory. It then uses WScript.Shell to execute both scripts, initiating the next stage in the infection process.

Figure 5 – Second-stage JavaScript files dropped into the %TEMP% directory

Each script acts as a component in a modular chain: the first decodes and writes files, while the second executes them. By breaking the infection chain into layers, the attackers minimize the chance of any one component being recognized as malicious.

Analyst Insight: This stage highlights a classic multi-stage JavaScript infection pattern relying on built-in Windows scripting components for stealth. Defenders should monitor for WScript or CScript executions from temporary directories, file creation under %TEMP%, and Base64-decoding behavior via Microsoft.XMLDOM objects — these are strong indicators of staged malware activity.

Stage 2: Dropping the .NET Loader

The second-stage scripts, adobe.js and svchost.js, function similarly to the first. They each contain another Base64-encoded payload.

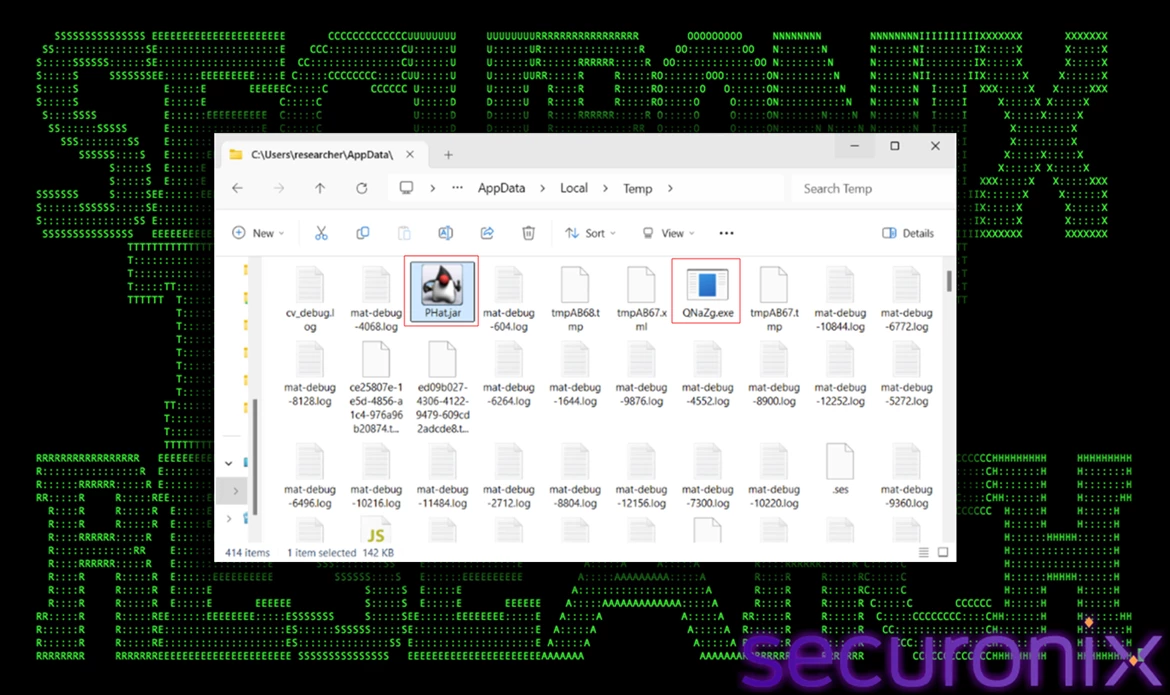

svchost.js drops the core component of the next stage: a .NET executable named QNaZg.exe, which is the DarkTortilla strain. It first checks the %TEMP% folder path using FileSystemObject and then decodes the embedded payload using MSXML DOM techniques. The decoded binary data is extracted via the nodeTypedValue property. Once the binary payload is accessible in memory, the script uses an ADODB.Stream object to write this data out to disk. The stream is initialized, configured for binary operations, and the decoded content is written directly to the stream. Before saving, the stream’s position is reset to ensure the full binary is written from the beginning of the file. The file is then saved to the temporary directory, with the overwrite option enabled to prevent errors if a file with the same name already exists. Finally, the stream is closed to release resources. Then it runs the dropped binary file using the WScript.Shell object.

adobe.js drops a file named PHat.jar, which our analysis revealed to be an MSI installer package. It behaves similarly to svchost.js.

Figure 6 – QNaZg.exe and PHat.jar dropped by the secondary scripts

Analyst Insight: This stage demonstrates DarkTortilla’s adaptability through the use of multiple loader types. The attackers leverage both a .NET executable and a Java-based package to maximize compatibility and reliability across systems. Defenders should monitor for script-based creation of executable or JAR files in %TEMP% directories, along with subsequent execution events via WScript or CScript. Unusual usage of ADODB.Stream for binary writes is a strong detection point.

Stage 3: The .NET Loader – Decryption and Reflective Loading

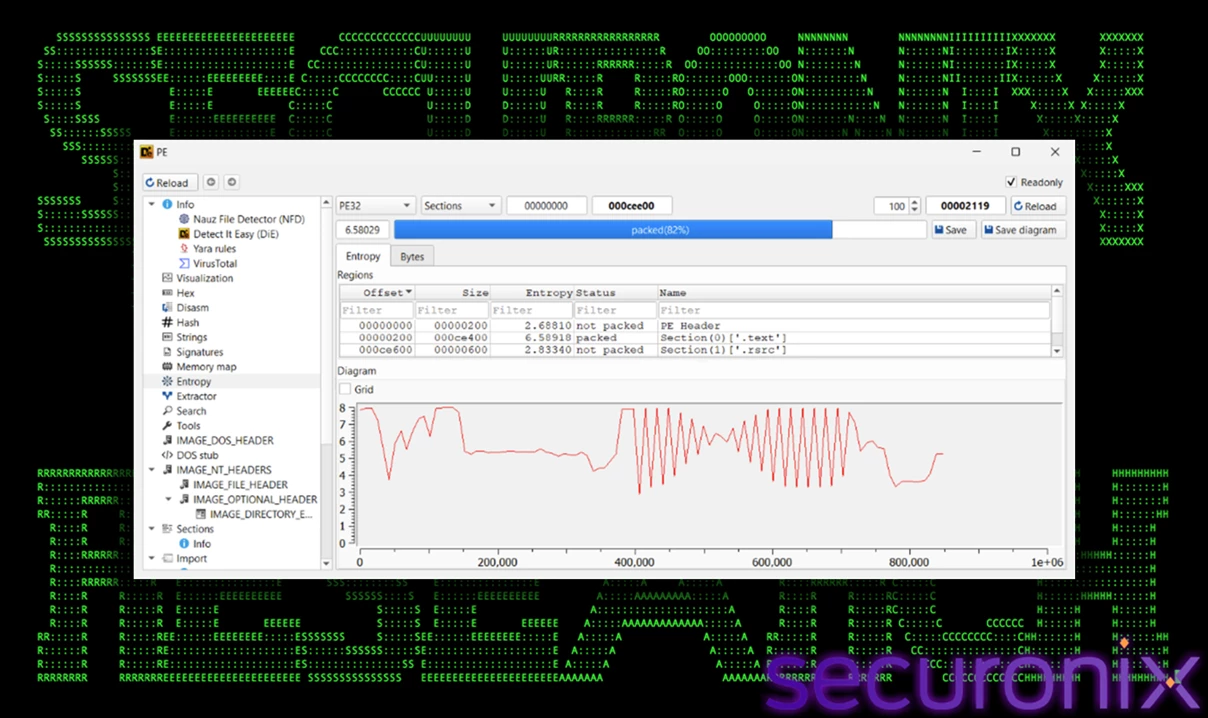

DarkTortilla (QNaZg.exe) is a 32-bit VB.NET executable that serves as the main loader for the final payload. Its high entropy suggests it is either packed or heavily obfuscated. It turns out to be heavily obfuscated (all classes and method names renamed or hidden).

Figure 7 – PE analysis of the .NET loader

This loader's primary responsibility is to decrypt and execute an embedded DLL stored within its own resources. This is accomplished through a multi-step process designed to evade analysis. The loader contains a large, hardcoded byte array, which is the encrypted final payload.

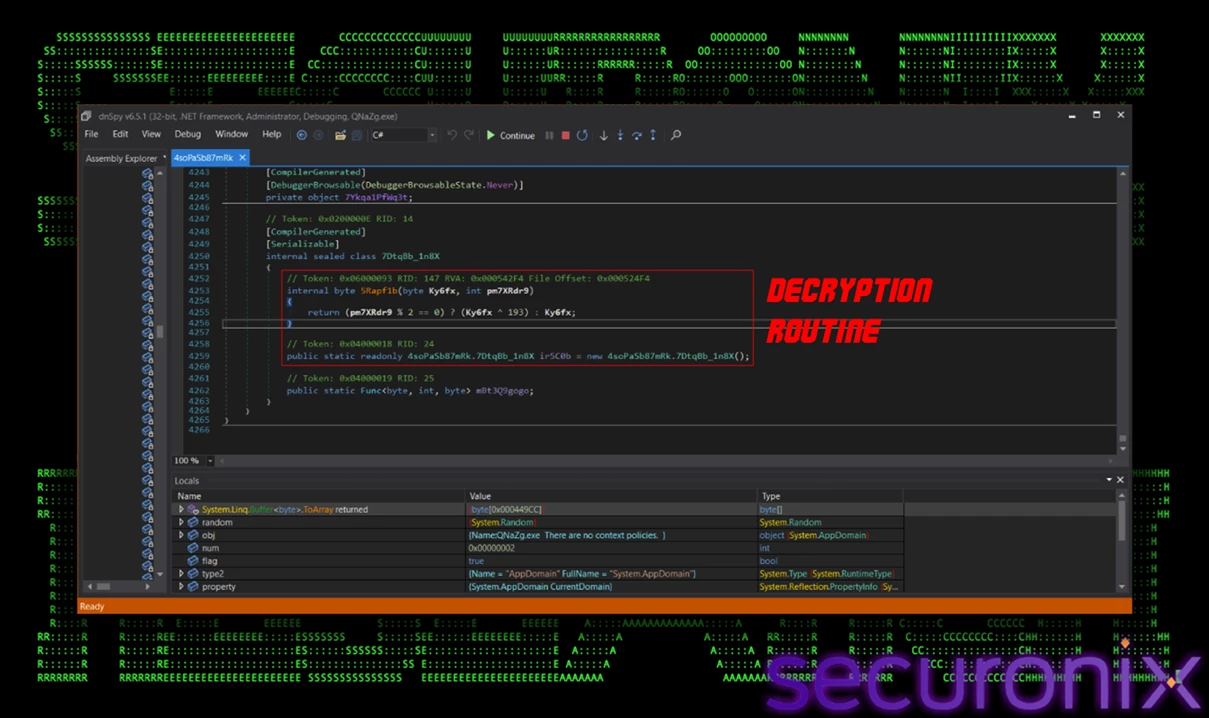

To decrypt it, the malware employs a custom algorithm:

- Reverse: The entire byte array is reversed using a LINQ

.Reverse<byte>()operation. - Conditional XOR: Each byte at an even index is XORed with the key

0xC1(193 in decimal); odd indices remain unchanged.

Figure 8 – Custom index-based XOR decryption routine

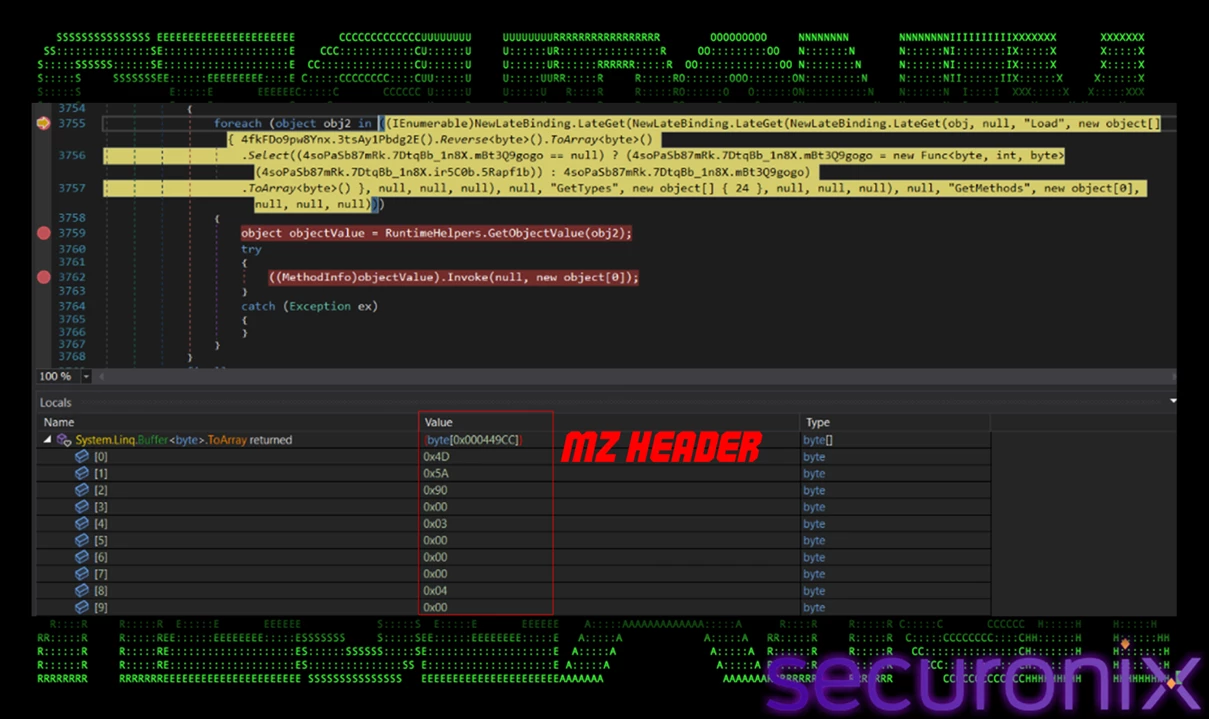

After decryption, the byte array reveals a valid PE file in memory, identifiable by the "MZ" header.

Figure 9 – Decoded DLL visible in memory

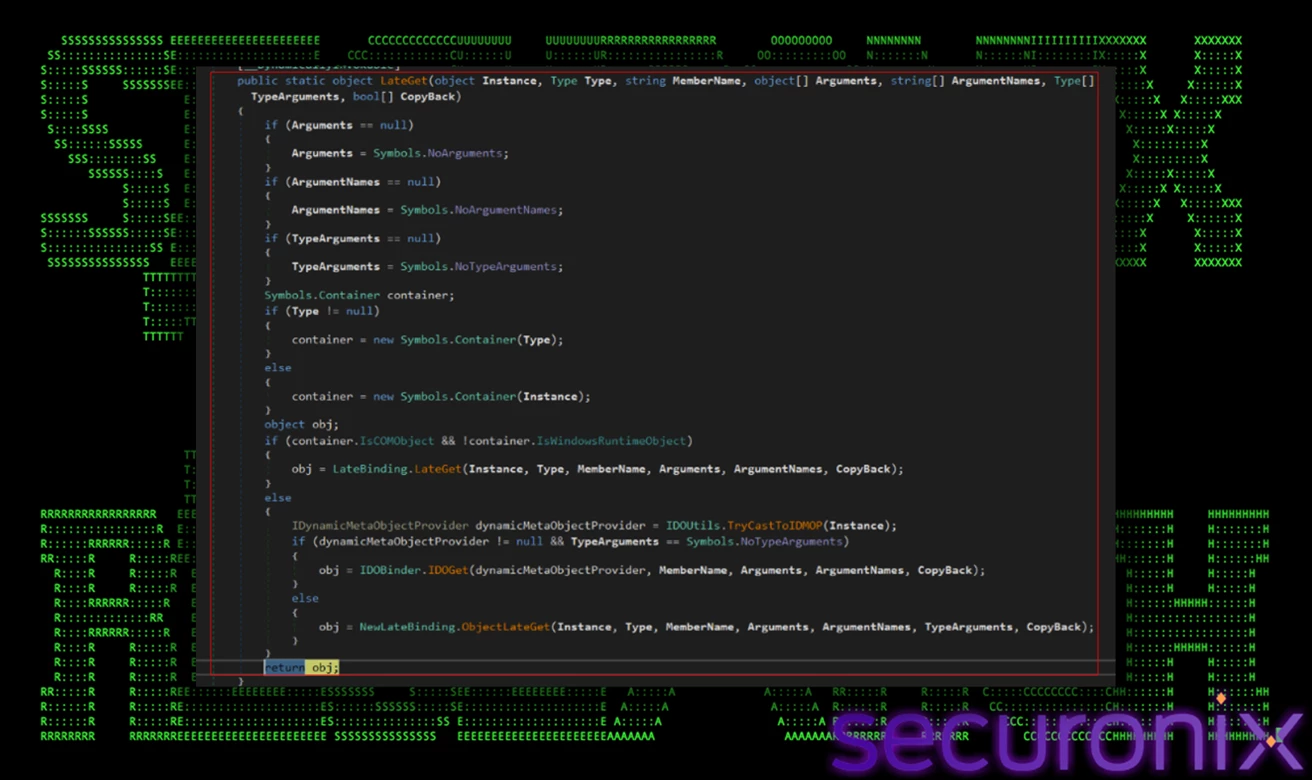

Reflective Loading and Late Binding

With the final payload assembly now fully decrypted in memory, the DARKTORTILLA loader orchestrates its execution in a manner designed for maximum stealth: reflective loading. This is a technique that completely bypasses the traditional Windows Portable Executable (PE) loader. Instead of writing the payload to disk as a physical file, the malware leverages the System.AppDomain.Load(byte[]) method. This instructs the .NET Common Language Runtime (CLR) to load the assembly directly from its byte array representation in the process's virtual memory.

Think of an AppDomain as a lightweight container within a process. A single OS process can host multiple AppDomains, each providing isolation for the code it executes. When launching a .NET application, it typically runs in a default AppDomain, which loads all assemblies into its space. Malware like DARKTORTILLA leverages AppDomain.Load(byte[]) because it enables loading a malicious assembly directly from memory, bypassing traditional detection that focuses on files written to disk.

Figure 10 – Reflectively loading the decrypted PE from memory

Once the payload is mapped into the application domain, the loader employs late binding and extensive .NET reflection to activate it. Instead of calling functions directly, it uses the Microsoft.VisualBasic.CompilerServices.NewLateBinding.LateGet() method to dynamically invoke the payload's entry point (Segwenservice.Class1_PreStart.Method0()). This allows runtime execution without compile-time linking, making static analysis extremely difficult.

Figure 11 – Using reflection to invoke the entry point of the in-memory payload

Analyst Insight: This stage highlights one of the most stealthy capabilities in modern .NET malware. By using reflective loading and dynamic invocation, the malware executes entirely in memory, leaving almost no artifacts on disk. Defenders can detect such behavior by monitoring for unusual use of AppDomain.Load(byte[]) in non-development processes and tracking reflection-based invocations. Memory forensics tools and behavioral EDR telemetry are critical in identifying fileless .NET threats.

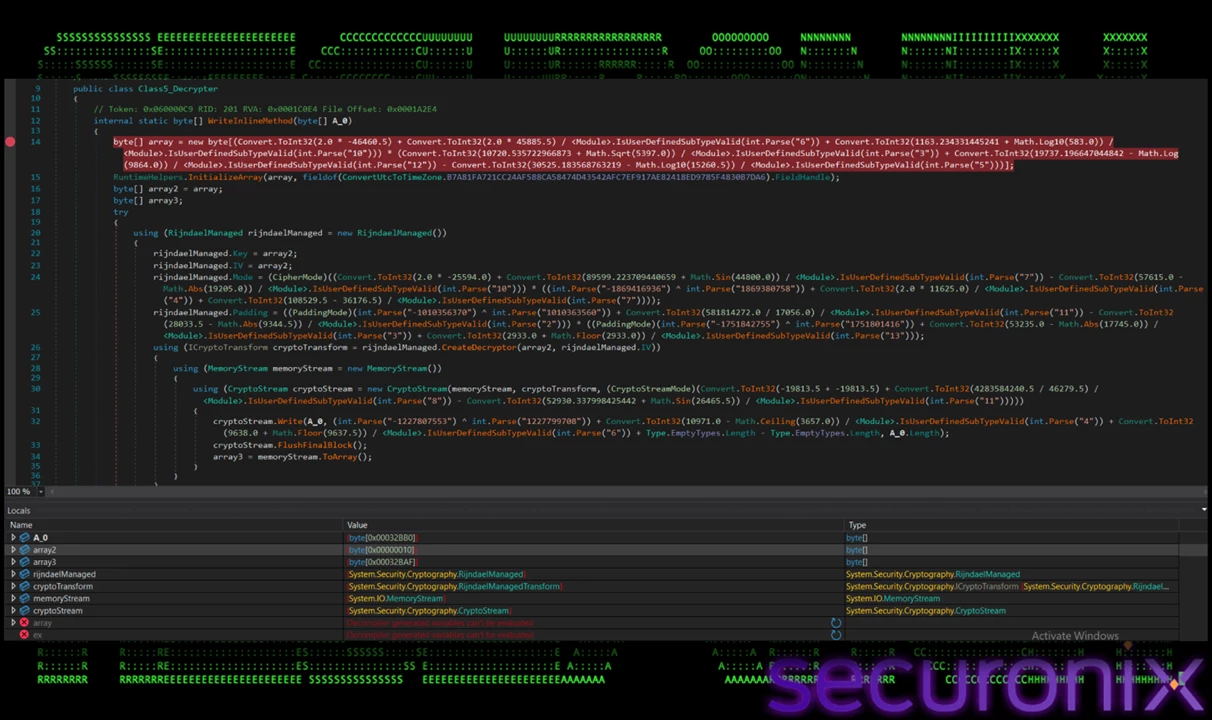

Stage 4: The Final Payload – FormBook RAT

The in-memory assembly, Segwenservice.dll, is the final payload, which we identified as a variant of the FormBook RAT. It is highly modular, with different classes responsible for specific tasks such as installation (Class11_Install), persistence (Class12_Startup, Class16_Persist), anti-VM checks (Class8_AntiVMs), and decryption (Class5_Decrypter). The malware behavior is dictated by a configuration file stored as an encrypted resource. This resource is decrypted at runtime using AES, making it difficult to extract its configuration without dynamic analysis.

Figure 12 – Decrypting configuration data containing persistence and behavior flag

The encryption routine that processes the encoded resource is a standard AES implementation. It decrypts via memory stream with a derived key IV. The decrypted AES byte array creates a binary reader over a memory stream from data, using UTF-8 encoding, and creates a list as a container. The list turned out to be a config which contains objects/key-value pairs. This configuration dictionary dictates the malware behavior, including persistence, installation paths, and anti-analysis features, which we will discuss in a moment.

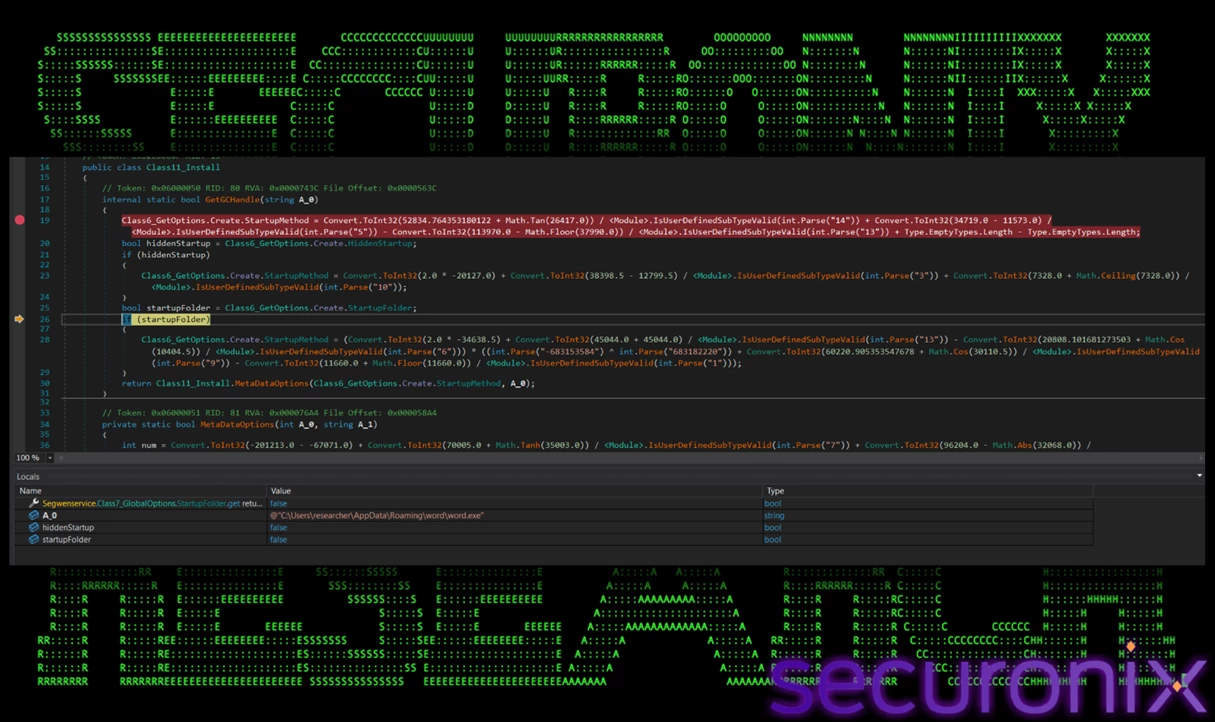

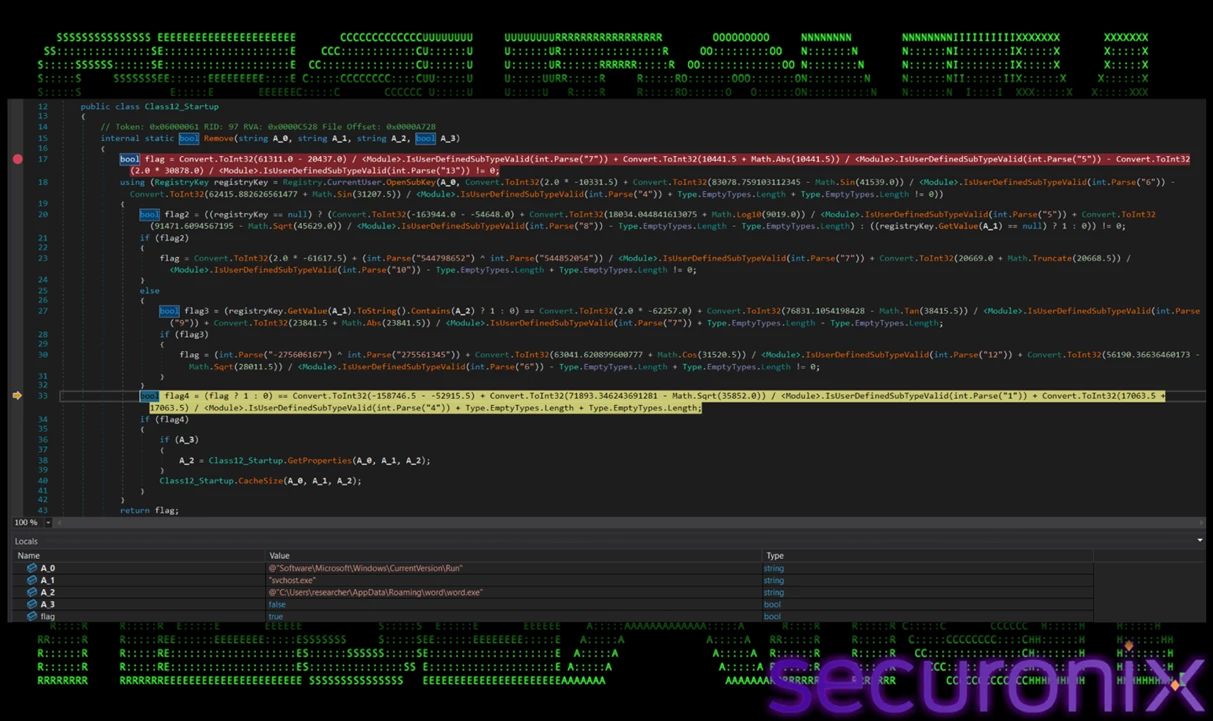

Persistence and Evasion

Based on its configuration, the RAT establishes persistence:

- File Placement: A command is constructed to copy the loader (

QNaZg.exe) to a new location:%APPDATA%\Roaming\word\word.exe, which is the startup folder, masquerading as a Microsoft Word component. It first checks for hidden startup/startup folder presence. By doing this, the malware ensures it will run again on reboot or login. Names like “word.exe” in a “word” folder in AppData are easily overlooked by users and many basic security controls. - Registry Run Key: It also manages persistence through the Windows Registry. It opens the registry run key under

HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Runand checks if a value with the namesvchost.exeexists. It then adds itself under Run, ensuring thatword.exeis launched at user login. The registry value name mimicssvchost.exe, which is a legitimate Windows system process.

Figure 13 – Malware drops itself into the startup folder

Figure 14 – Persistence using registry run key

Anti-Analysis: Bypassing Automated Sandboxes

The malware anticipates being run in automated analysis environments and employs a classic technique to defeat them. It constructs and executes a cmd.exe command that includes two ping 127.0.0.1 -n 39 > nul commands.

cmd /c ping 127.0.0.1 -n 39 > nul && copy "C:\Users\\AppData\Local\Temp\QNaZg.exe""C:\Users\\AppData\Roaming\word\word.exe" && ping 127.0.0.1 -n 39 > nul &&"C:\Users\\AppData\Roaming\word\word.exe"

Each ping command introduces a delay of approximately 38 seconds. Many automated sandboxes terminate analysis if a sample appears inactive for too long. By introducing these delays, the malware outlasts the sandbox timeout, hiding its full behavior.

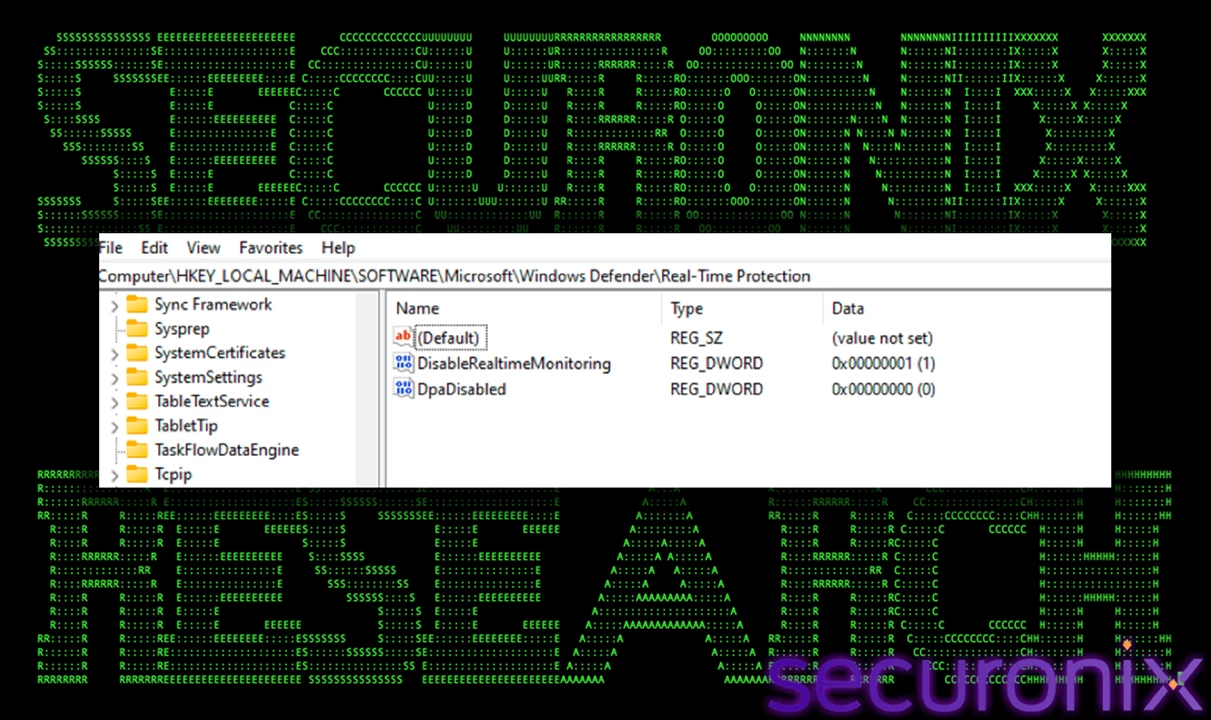

Our analysis observed the RAT attempting to modify registry keys associated with Windows Defender to disable its real-time monitoring. This reduces the likelihood of detection by built-in endpoint protection.

Figure 15 – Windows Defender disablement

Analyst Insight: This stage highlights FormBook’s focus on persistence and long-term access. The dual persistence strategy ensures reliability, while disabling security tools hinders detection. Defenders should monitor HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run for suspicious keys referencing AppData executables and track delayed command execution involving ping 127.0.0.1 -n patterns, which often indicate sandbox evasion.

Keylogging Functionality and Data Exfiltration

A primary function of the FormBook RAT in this campaign is pervasive keylogging. The malware implements a low-level keyboard hook (using Windows APIs) to intercept keystrokes across all applications. This allows it to capture every key pressed by the user, regardless of the active window.

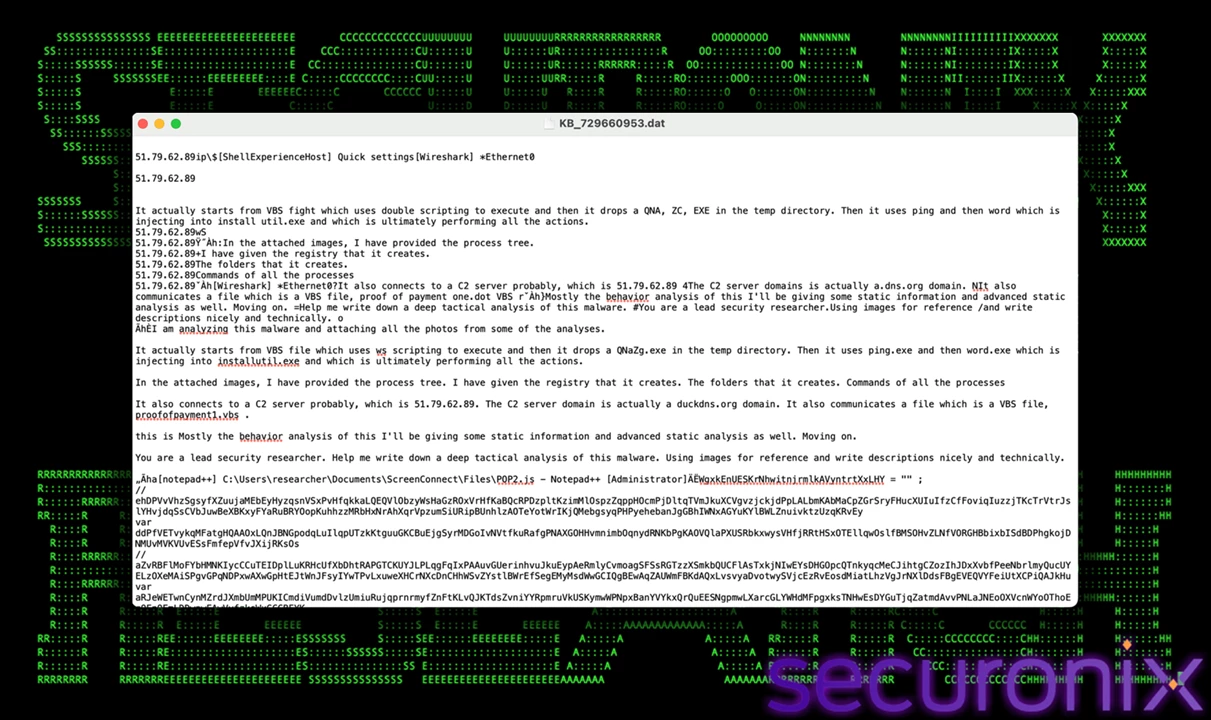

The captured keystrokes are buffered and written to local files for later transmission. During our analysis, the RAT created files matching the pattern KB_*.dat (e.g., KB_2025-10-07.dat) in its persistence directory (%APPDATA%\Roaming\). This batching minimizes network traffic and ensures data persistence even if the C2 server is temporarily unreachable.

Figure 16 – Log file created by RAT

Each log file follows a structured format that distinguishes special keys (e.g., Shift, Ctrl, Alt, Enter, Backspace) using tagged or bracketed labels. This format simplifies parsing and data analysis by attackers.

Analyst Insight: FormBook’s keylogging feature is designed for both persistence and stealth. Since the logs are locally buffered, defenders can hunt for file naming patterns like KB_*.dat within %APPDATA%\Roaming. EDR telemetry can also reveal the creation of hidden hooks or consistent file writes by unauthorized processes.

Command and Control (C2) Infrastructure

The FormBook RAT initiates outbound connections to its command and control (C2) infrastructure to receive instructions and exfiltrate collected data. During analysis, the RAT attempted to connect to a dynamic DNS domain (duckdns.org), resolving to 51.79.62[.]89, primarily over TCP port 57652.

Dynamic DNS services allow threat actors to change backend IP addresses frequently while maintaining the same domain, complicating defensive blocking and analysis. Network captures confirmed multiple connection attempts to the C2 host during execution.

Analyst Insight: Dynamic DNS-based C2 infrastructure remains a common tactic for malware operators. Defenders should monitor outbound traffic to DDNS domains (e.g., duckdns.org), especially over non-standard ports. DNS query logging and network flow monitoring can reveal patterns consistent with FormBook RAT activity or DarkTortilla loader communication.

Wrapping up…

The DARKTORTILLA campaign demonstrates a sophisticated, multi-layered approach to malware delivery. The threat actors combine social engineering, heavy script obfuscation, and advanced .NET evasion techniques to successfully compromise targets. The use of a custom decryption routine followed by reflective loading allows the final payload to be executed in a fileless manner, significantly complicating detection and forensic analysis. By masquerading its files and registry keys with legitimate-sounding names, the malware attempts to blend in with normal system activity to maintain long-term persistence.

Analyst Insight: Defenders should prioritize layered controls that correlate script execution from %TEMP%, reflective .NET assembly loading, delayed command execution (e.g., ping 127.0.0.1 -n <N>), and registry-based persistence in HKCU\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Run. Behavioral EDR rules targeting in-memory assembly loads (e.g., AppDomain.Load(byte[])) plus alerting on ADODB.Stream writes and Microsoft.XMLDOM Base64 decoding provide practical detection choke points across the chain.

Victimology and Attribution

This campaign appears to primarily target organizations in the National Social Security Sector. The social engineering lures are tailored to this specific vertical. Currently, there is not enough information to definitively attribute this campaign to a specific country or threat group.

Securonix Recommendations

- User Awareness: Maintain vigilance against social engineering attacks and educate users to never download or execute files from untrusted web portals or emails.

- Source Validation: Always verify that software downloads come from legitimate and official websites.

- Endpoint Security: Deploy a strong defensive solution capable of monitoring for suspicious script execution, reflective loading of .NET assemblies, and unusual parent-child process relationships (e.g.,

word.exespawningInstallUtil.exe). - Script Execution Policies: Enforce strict script execution policies, such as blocking

.jsand.vbsfiles from the internet via email gateway rules or application control. - Enhanced Logging: Enable enhanced command-line and PowerShell logging to capture obfuscated commands and fileless attack stages for investigation. Implement keyboard event logging and monitor file creation in

%APPDATA%for suspiciousKB_*.datpatterns.

Securonix customers can scan endpoints using the Securonix hunting queries below.

MITRE ATT&CK Matrix

| Tactics | Techniques |

|---|---|

| Initial Access | T1566.002: Spearphishing Link |

| Execution | T1059.007: JavaScript T1059.003: Windows Command Shell |

| Persistence | T1547.001: Registry Run Keys / Startup Folder |

| Defense Evasion | T1021.007: Remote Services: Cloud Services |

| Execution | T1027: Obfuscated Files or Information T1140: Deobfuscate/Decode Files or Information T1620: Reflective Code Loading T1036.005: Match Legitimate Name or Location T1562.001: Disable or Modify Tools (Windows Defender) T1497.003: Time Based Evasion (Ping Delay) |

| Credential Access | T1056.001: Input Capture: Keylogging |

| Command and Control | T1571: Non-Standard Port T1568.002: Dynamic Resolution: DGA (duckdns.org) |

Relevant Securonix detections

- Suspicious Javascript Execution From Temp Location Analytic

- Startup Run Registry Key Created to Suspicious Directory Analytic

- Potential Windows Defender Modification Registry Analytic

Relevant hunting queries

(remove square brackets “[ ]” for IP addresses or URLs)

index = activity AND rg_functionality = "Next Generation Firewall" AND destinationaddress = "51.79.62[.]89"index = activity AND rg_functionality = "Endpoint Management Systems" AND deviceaction = "File created" AND filename IN ("QNaZg.exe", "adobe.js", "svchost.js", "word.exe")index = activity AND rg_functionality = "Endpoint Management Systems" AND deviceaction = "Process Create" AND ChildProcessCommandLine CONTAINS "ping 127.0.0.1 -n 37 > nul &&"index = activity AND rg_functionality = "Endpoint Management Systems" AND deviceaction CONTAINS "Registry value set" AND eventtype = "SetValue" AND targetobject CONTAINS "SOFTWARE\\Microsoft\\Windows\\CurrentVersion\\Run\\svchost.exe"index = activity AND rg_functionality = "Endpoint Management Systems" AND SourceProcessName IN ("wscript.exe", "cscript.exe") AND deviceaction = "Process Create" AND childprocesscommandline CONTAINS "AppData\\Local\\" AND childprocesscommandline CONTAINS ".exe"index = activity AND rg_functionality = "Endpoint Management Systems" AND image CONTAINS "InstallUtil.exe" AND parentimage CONTAINS "word.exe"C2 and infrastructure

| C2 Address |

|---|

| 51.79.62[.]89 Associated duckdns[.]org domain |

Analyzed files/hashes

| File Name | SHA256/MD5 |

|---|---|

| part1 | eba24c92b51d8fb24697952135a7d7bdf4a7511ab94be850fda1fc512675f6ad |

| 81__POP1.BZ2 | 67c00ede3964cb78c64575b65b301f808958311b99779b71597f6282b1a4e9f2 |

| PROOF OF PAYMENT1.vbs | 4ebef5d23ce0fe6c2940ba7a2f6bfc512b1ec5f01458284d2ce0e71ee8787b81 |

| POP2.js | d4c097412ab05630e6cb97b544dc7c0a0e238a4bdf5c79da679c7545face2dad |

| svchost.js | aab2b9cd5a946739bbb41ae2234adaf34ba9761445315c2b5ba270a7b931a2e2 |

| adobe.js | 56d627adc6e6e8967ade649f707134a501cfea5ec66322514536ee8ace3053fb |

| PHat.jar | 7c9128d197301fcd89d6fd1b0077d2a35f2a98c6219386900d7e8c89e4799a86 |

| QNaZg.exe | a428d2602ad3bad2d590ed68b17a308cff8ab7ff61da2a51acb83fd202b5358d |

| Segwenservice.dll [embedded payload] | 8bcfc6dd444f3f577f026d465d826194db45cd205b24f77b9080debba96e3b7b |

🧠 Threat Research Collaboration

If you’ve encountered DarkTortilla or FormBook variants in the wild, we’d love to hear your observations.

Comment below or tag our Threat Research team on the Securonix Connect Community to exchange detection ideas and threat intelligence.